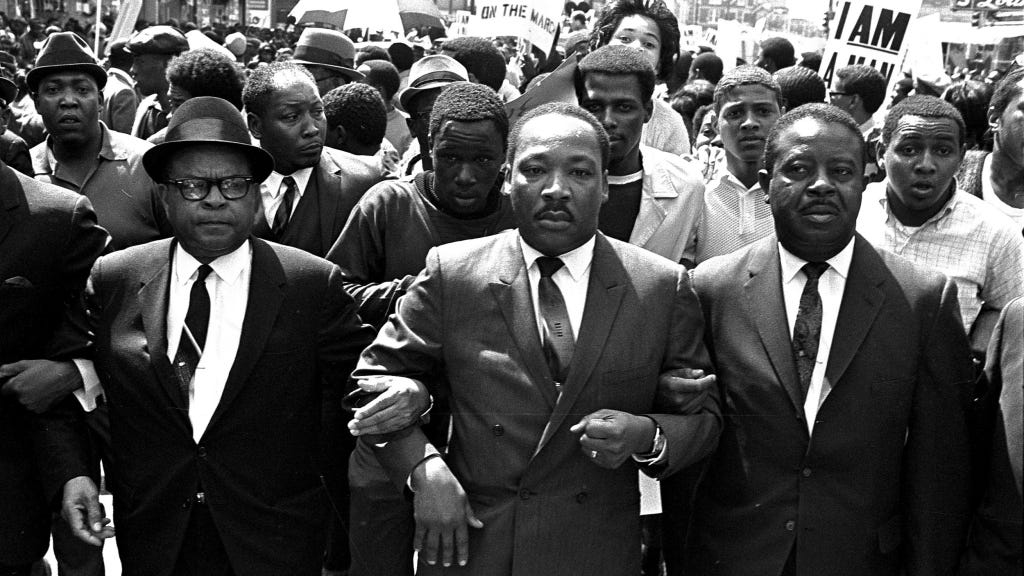

An old way to be antiracist

“We allowed ourselves to accept middle-class prejudices against the labor movement…In shunning it, we have lost an opportunity. Let us try to regain it now, at a time when the joint forces of Negroes and labor may be facing a historic task of social reform.”

-Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Photo: AP/Jack Thornell

I recently emailed my advisors to let them know that I want to defend my dissertation by the end of this year. After seven years of graduate school, I am ready to defend my conclusions about racism and racial inequality in higher education to them and the rest of my committee of brilliant, critical scholars. More important, at least to me, I’m ready to look for job that pays me enough to help support my family.

I’m not gonna lie…I’m really nervous. As a remedy, this nervous nerd would love to know if their argument is persuasive before I present it to my committee. To quickly summarize: in what follows, I will defend the argument that one way to be an antiracist is to support the unionization of employees. I would love to know your thoughts before I publish start sharing this argument with a wider audience.

____________________________________________________________________________

One of the reasons why I prefer the book How to Be an Antiracist over the popular alternative, White Fragility, is that the author presents a more useful definition of anti-racism. Rather than focusing on the hearts and minds of individuals, historian Ibram Kendi suggests that anti-racism cannot be disconnected from politics. Specifically, Kendi’s argument can be summarized as follows: an antiracist is someone who supports policies that can reduce (or even eradicate) the unjust treatment of people on the basis of their racial identification. By offering this definition, Kendi invites readers to consider how they can work to change the official and unofficial rules that govern social action on a macro-level (such as the state) and a meso-level (such as schools, businesses, and other organizations).

My dissertation asks a follow-up question to How to Be an Antiracist: what policies should antiracists—or people who are genuinely trying to be antiracist—actually support?

Seven years ago, when I started graduate school at Boston College, I thought an antiracist was someone who supports a policy like mandatory diversity trainings. I even helped provide something like a diversity training on microaggressions during my senior year at Ithaca College. However, while conducting my research on diversity workers in higher education, I made two discoveries that completely shattered my assumptions about anti-racism.

First, I learned that there are legitimate reasons to question the belief that diversity trainings reduce racism and racial inequality. It is an unfortunate and inconvenient truth that the research on anti-discrimination practices suggests that diversity trainings may not only be ineffective, but they may even lead to an increase in racial inequality. Putting it mildly, it is hard for me to demonstrate that a policy of mandatory diversity trainings is “antiracist” if it fails to lead to a reduction in racism and racial inequality.

The second discovery I made during my research is that fear of retaliation shapes how professional antiracists (such as diversity managers) respond to complaints about racism and racial inequality at postsecondary schools. For example, I asked over two dozen diversity and inclusion professionals participants some version of the following question: if anti-racist protestors provided reasonable complaints about a school president’s policies and practices, should we expect diversity workers to publicly support their resistance? While they would look for ways to privately support the protestors, almost every single person expressed the view that we should not expect them to publicly support resistance to the president’s policies and practices. The main theme in their explanations was fear of retaliation.

To be clear, I do not believe that this finding can be reduced to the hearts and minds of the professional antiracists. Instead, I believe that this finding can be attributed to the fact that they tend to be at-will employees, meaning the president can dismiss them for any reason at any time (except for an illegal reason, such as racial discrimination). If they supported demands to remove the president of the college for racist policies and practices, for example, then it is reasonable for those professionals to expect that they will soon be unemployed. As one participant mentioned several times in the course of an interview, there are no “tenure” protections for most diversity and inclusion professionals like there is for some college professors.

After learning that diversity trainings may be ineffective and at-will employment is a structural constraint for diversity workers, I have concluded that it is reasonable for an antiracist to support policies that provide protections for people who push for organizational change. One way to accomplish this goal is to support the unionization of employees.

Unionization is rarely mentioned as “a case of” antiracism. However, there are at least four good reasons to treat unions as a better approach to antiracism than supporting diversity trainings. First, it is generally harder for employers (including racist employers) to fire antiracist activists or anyone who complains about racism in an organization than employees who are supported by a union than employees without a union. As historian Toure Reed demonstrates in his book Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism, “To be sure, liberals and progressives did not always separate race from class. Influenced by New Deal industrial democracy, civil rights and labor leaders of the 1930s and 1940s generally presumed that racism was inextricably linked to class exploitation. Civil rights leaders of this era thus identified interracial working-class solidarity as essential to racial equality” (p. 10). In short, the struggle for civil rights was intimately connected with the labor movement.

Second, a recent study suggests that unionization can lead to a reduction in racist beliefs. In a recent piece for the Jacobin, Megan Day provides a great summary of the findings when she writes:

“The study, conducted by Paul Frymer of Princeton University and Jacob M. Grumbach of the University of Washington, evaluated white people’s responses to statements that effectively deny the existence of racism — for example, “It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.” They found that white union members are less likely to have racist attitudes than white workers in similar industries who are not in a union, becoming a union member reduces white workers’ racial resentment, and even that formerly being a union member reduces white workers’ racial resentment. That lessening of racial resentment even translates, they write, to increased support for policies that benefit African Americans like affirmative action.”

Thirdly, unions can provide a more democratic approach to anti-racism and civil rights enforcement in the workplace. For example, without a union, some employees can rely on a diversity manager to address their grievances about discrimination or harassment. While the person working as a diversity manager could be a fierce advocate for antiracism, the diversity manager is neither selected by nor accountable to the complainant. Instead, the diversity manager is selected by and accountable to the most powerful member of the organization: the president. Therefore, the interests and expectations of the president shapes how that diversity manager will respond to the complaint. On the other hand, if a union member has a complaint about discrimination or harassment, they have access to a steward that can advocate for remedies on their behalf. That steward is someone who is selected by and accountable to workers, and they are not paid to align the behavior of employees with the interests of bosses and management. This difference matters because the majority of people identified as racial minorities are workers, not managers or employers.

Lastly, it is no secret that unions can compel employers to provide better wages for their employees of all racial identifications. I don’t know anyone who would choose the most popular anti-discrimination practice (diversity trainings) over a contract that can increase their wages and other benefits. At the very least, I would choose better wages over a diversity training any day.

In conclusion, I genuinely believe that racism is a problem that needs to be addressed. The question, then, is what mechanisms can actually lead to a reduction in racism and, consequently, racial inequality? After studying diversity work in higher education for my dissertation, and seeing how at-will employment functions as a constraint on the ability of professional antiracists to address complaints about organizational policies and practices, I have concluded that an antiracist can be someone who supports unions.

Yup. Any way you put it -- be it the Selznick (1957) style "capture" of diversity work by uni president interests [sociology], or an intra-org variant of Pfeiffer & Salancik (1978) "resource dependence" [Org Behavior], or a case of the Briscoe & Gupta (2016) dilemma facing "insider activists" for social movements [Social Movement theorists] --> you are making a major contribution. The at-will employment status, a dependence mechanism, is answered by unionization. You're making theoretical and practical contributions that several fields need to hear.

This King quote is 🔥🔥